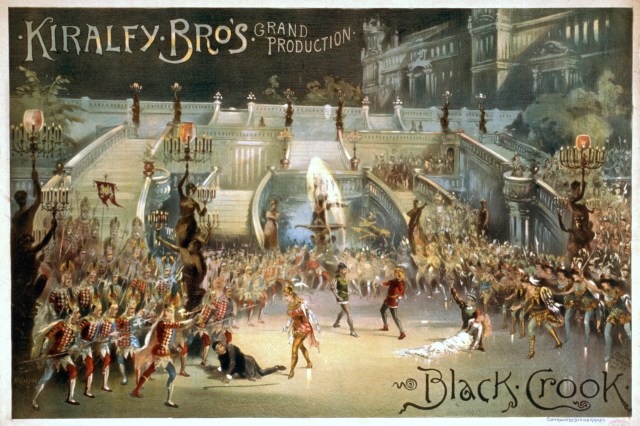

Musical theatre, as we know it today, is a fabulous hybrid form, one that grew out of many traditions rather than springing fully formed from a single moment. And yet, we tend to fall into the habit of simplifying Broadway’s origin story, partly because it’s so rich and complex, which ironically makes it all the more interesting! In many retellings of Broadway’s history, the 1866 premiere of The Black Crook has been held up as the first musical, comedy, or at least the first recognisably modern one. However, most contemporary scholars agree that this label doesn’t really hold. Earlier shows had already blended music and story, and stylistically, The Black Crook was more a patchwork of existing forms than a clean leap into the future, with little deliberate intention guiding its creation. Nonetheless, its impact was real. Its success helped establish a new culture of theatre-going on Broadway, one that bridged elite audiences who looked to Europe for cultural validation and the more worldly crowds who embraced popular entertainment in districts like the Bowery. So if The Black Crook wasn’t the sole birthplace of the Broadway musical, what else shaped the form we recognise today? This week’s Saturday List looks back at five theatrical traditions that did more to establish the conventions of the Broadway musical than The Black Crook did, even if traces of all of them can be found in that famously unwieldy nineteenth-century spectacle.

5. The Ballad Opera

If the Broadway musical has a basic engine, it’s this: dialogue gives way to song, which then returns us to the scene, a rhythm so familiar that we barely notice it or understand how difficult it can be to achieve well. That structure comes straight from ballad opera. Ballad operas were comic plays peppered with popular tunes, reset to new, often satirical lyrics. The most famous example remains The Beggar’s Opera, although Flora, or Hob in the Well just beat it to the American stage. The tone of many of our favourite musicals also found its first expression here, though the use of irony, the inclusion of social commentary, and the employment of a knowing wink at the audience. Crucially, ballad opera paved the way for early American musicals, which were essentially comic operas, which included original scores. Their influence didn’t vanish with the eighteenth century. You can hear it clearly in The Threepenny Opera, and later still in the work of Kander and Ebb, particularly Cabaret and Chicago, where popular musical styles are weaponised to critique the world they depict.

4. The Extravaganza

Before Broadway learned restraint, it learned spectacle. Extravaganzas emerged in the mid-nineteenth century, blending music, dance, burlesque and visual effects to create an elaborate evening of entertainment. Pretty much almost anything could be labelled an extravaganza, provided it dazzled the audience. Although French fairy spectacles helped shape the form, the American version quickly took on a flavour of its own. By 1855, shows like Pocahontas, a burlesque that was later picked up by blackface minstrel troupes, pointed the way forward. Burlesque extravaganzas like this one spoofed everything at once: history, literary classics, public figures political events. Another frequent inclusion in extravaganzas a transformation scene, in which the scenic design of the stage changed before the audience’s eyes. That expectation of this kind of miraculous transformation never really went away. From Boris Aronson’s jaw-dropping designs for Follies to the automated marvels of the megamusical era, extravaganza trained audiences to hope for this kind of coup de théâtre, a moment where theatre reminds us of its own magic.

3. Pantomime

Pantomime often began with contemporary characters who were magically transformed, frequently by a fairy, into stock commedia dell’arte figures, complete with masks and stylised movement. Around them existed a second set of performers, actors who spoke and sang normally, grounding the fantasy in something more recognisably real. Originally only forming part of a more extended programme, the plots of pantomimes were usually borrowed from nursery rhymes or fairy tales, although fidelity to source material was never the point. Pantomime existed to showcase the performers’ talents, including comic turns, singing, dancing and impersonation. Big-budget productions added scenic tricks and stage transformations that left audiences gasping, incorporating the influence of extravaganzas and burlesque. Full-length pantomimes followed. In 1868, Humpty Dumpty, ran for 483 performances, surpassing the popularity of The Black Crook. From there, the leap to Babes in Toyland, and eventually to Broadway’s modern family spectacles, from Beauty and the Beast onwards, feels remarkably small.

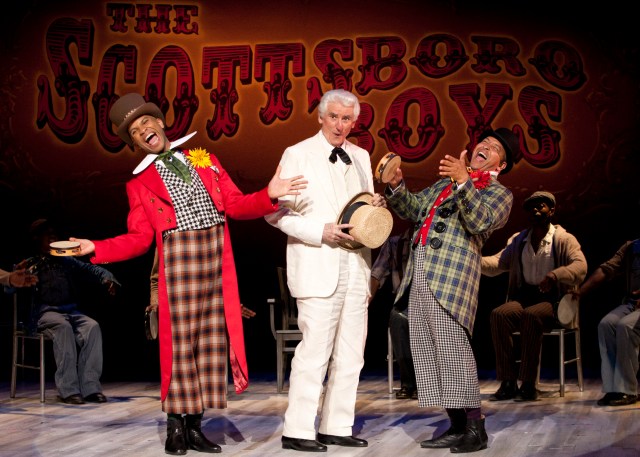

2. Minstel Shows

There is no way around this: minstrel shows were racist and demeaning. Blackface performance is inseparable from their legacy. As such, minstrelsy occupies an uncomfortable but crucial place in musical theatre history. Minstrel shows were the first form of musical theatre that was entirely American-born. Black and white performers both performed in minstrel shows, which were supported by audiences of all races. Structurally, they were surprisingly sophisticated. The three-part format, including the introductory minstrel line with its stock characters, the variety acts that made up the olio, and the one-act musical burlesque that was presented as the afterpiece introduced patterns of musical storytelling that would endure for decades. Minstrelsy’s popularity faded as audiences demanded more aesthetically refined entertainment, although its influence lingered into the twentieth century, particularly in smaller towns, before cinema finally sealed its fate. Its legacy is troubling, but its structural imprint on American musical theatre is undeniable.

1. Variety

In muiscal theatre terms, variety paved the road to vaudeville. Early variety entertainment was scandalous. It thrived in saloons where so-called “respectable women” were forbidden to set foot and waiter-girls served drinks – and more – to their gentelmen patrons. Although police raids were frequent, this discouraged neither the saloons’ owners nor their patrons. Over time, variety evolved, shedding its shadier reputation and sharpening its entertainment value. Major musical stars like Lillian Russell turned up on variety bills, lending prestige to what had once been considered disreputable. Variety’s emphasis on star turns, pacing and audience pleasure fed directly into vaudeville, which would dominate American popular entertainment in the years following The Black Crook. The influence on musical theatre was enormous. Variety and vaudeville trained audiences to expect momentum, clarity and personality, qualities that Broadway musicals would increasingly prize as they moved into the twentieth century.

Rethinking the Broadway Musical’s Origin Story

Revisiting these forms reminds us that the Broadway musical didn’t emerge overnight. It was built from many ingredients. Some were joyous and others, troubling. All were influential. The Black Crook may still mark a turning point, but it was never the whole story. The more interesting question might be this: which of today’s theatrical forms – immersive theatre, jukebox musicals, digital hybrids – will still be shaping musical theatre a century from now? History suggests that the answer may surprise us.