In the four decades since Merrily We Roll Along flopped on Broadway, effectively bringing Stephen Sondheim’s prolific collaboration with director-producer Harold Prince to a painful end, Sondheim wrote only six new musicals for the stage: Sunday in the Park with George, Into the Woods, Assassins, Passion, Road Show and Here We Are, the last of which premiered posthumously. Prince did, of course, collaborate with Sondheim on an earlier version of Road Show, then titled Bounce, but that project never quite found its footing. With a high-profile revival of Sunday in the Park with George starring Jonathan Bailey and Ariana Grande announced for 2027, this feels like a great moment to revisit and rank Sondheim’s post-Prince works. Each of these shows has something valuable to offer, even if they are not equally loved, equally understood or equally easy to embrace.

6. Road Show (2008)

A decade in the making, Road Show finally arrived in 2008 after a long and complicated gestation, having been seen earlier as a workshop in 1999 and as Bounce in 2003. Created in collaboration with John Weidman, Road Show was inspired by the lives of brothers Addison Mizner and Wilson Mizner, a kind of modern American fable that took audiences from the Klondike gold rush of the 1890s to the Florida real estate boom of the 1920s. Expectations were high. Audiences hoped for another Company or Follies; what they got was something smaller, stranger, and far more elusive. For many, that was reason enough to write the show off entirely – myself included, for a time. But revisiting Road Show once the hype had faded revealed more than memory suggested. There is strong material here, including “Addison’s Trip,” “Talent” and the universally loved “The Best Thing That Ever Has Happened.” Its greatest weakness may be that it feels as though it has less to say than Sondheim’s towering achievements. Still, I wonder what a genuinely fresh production, one unburdened by expectation, might uncover. It is unlikely to climb much higher on this list, but it remains more intriguing than its reputation suggests. Its 2019 outing at New York City Centre seems to be evidence of just that.

5. Here We Are (2023)

Here We Are, Stephen Sondheim’s final musical, with a book by David Ives based on the films The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and The Exterminating Angel by Luis Buñuel, arrived posthumously. It follows a group of wealthy, self-absorbed characters attempting to have brunch while society quietly collapses around them. Encountering the cast album made one thing immediately clear for me: despite early speculation, the score does not feel unfinished. As Ives and Joe Mantello, the director of the premiere production, explained, Sondheim stopped writing when the characters had nothing left to sing. Content dictated form. Musically, Here We Are belongs firmly to Sondheim’s later approach to integration, closer in structure to Passion and Sunday in the Park with George than to his earlier works. Its pleasures lie in its momentum and texture, and in exquisite lyrical detail rather than obvious set pieces. Numbers like “Waiter’s Song,” “It Is What It Is” and “Shine” balance wit with unease in the best tradition of Sondheim’s works. Considered alongside his other musicals, Here We Are can feel like a piece that is still finding its place. Time may yet reshape how we understand it, but even now it stands as a thoughtful, unsettling and unmistakably Sondheimian show.

4. Into the Woods (1987)

Into the Woods, the fairy tale mashup Sondheim created with James Lapine, has become increasingly difficult for me to appreciate simply because of its ubiquity. Telling the story of a Baker and his wife, who cross paths with Cinderella, Jack and his beanstalk, Little Red Riding Hood, Rapunzel and – of course – a wickedly glamorous witch, the show asks us to consider the importance of community and how we connect with one another. From the turn of the century onwards, it feels like this show has been everywhere, endlessly produced, reimagined, reinterpreted and reinvented. Child narrators, radical design concepts and revisionist framings abound. While it’s actually amazing to see the piece tackled with such love, diversity and vitality, it does make it a little more challenging to return to the show on your own terms. Nonetheless, I was certainly able to discover its pleasures again when I directed it for a local high school. My advice now is the same advice I gave myself back then: clear your mind, return to what was there at the beginning and let your imagination do the rest. The show’s popularity may sometimes obscure its precision, but its rewards remain intact for those willing to listen closely. “Children Will Listen,” indeed.

3. Passion (1994)

Many people hate Passion with an intensity that borders on the visceral. Some even claim it is a bad show. It isn’t. Based on Ettore Scola’s film Passione d’Amore, Passion was the last of Sondheim’s three collaborations with James Lapine and holds the distinction of being the shortest-running Tony Award-winner for Best Musical ever. Set in nineteenth-century Italy, the show examines the obsessive love of Fosca for a young soldier, Giorgio, and the transformation this obsession affects in him. It is a work that demands emotional maturity, not in terms of age, but in terms of experience. What you bring to this show profoundly shapes what you take from it. Passion is intimate, uncomfortable and deeply personal. It cuts close to truths many people would rather not confront. In my opinion, this discomfort is precisely why some audiences struggle with it. As such, people need to approach Passion with openness and curiosity. If you still reject what it has to say, that’s fine, but recognise that dislike does not equate to poor craftsmanship. This is one of Sondheim’s most rigorously constructed and emotionally challenging scores – with some especially memorable highlights in songs like “I Read,” “I Wish I Could Forget You” and “Loving You.”

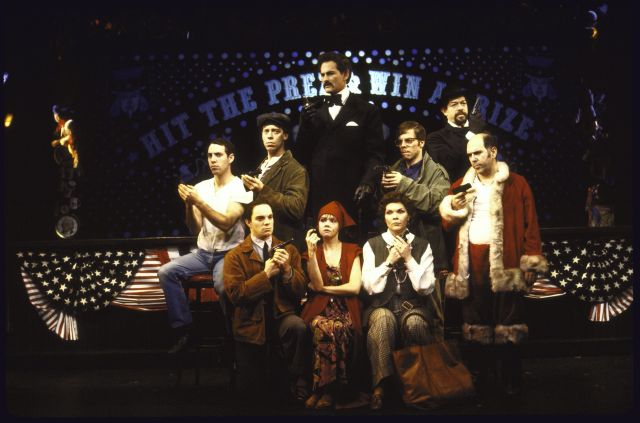

2. Assassins (1990)

I love Assassins. It is a brilliant show, though I will admit I preferred it before “Something Just Broke” was added to the score. To be honest, I’ve softened on that song over time, but my ambivalence remains. Using the macabre framing device of an all-American carnival game, Assassins, which Sondheim wrote with John Weidman, examines one of the darkest threads in American history: people who murdered, or attempted to murder, American presidents, and the distorted ideals that fuelled their actions. Many fans of the show recommend that newbies start off by listening to the Broadway cast recording. I’d argue instead for the earlier Off-Broadway album, which preserves a crucial scene from the show that wasn’t recorded for the revival. Both casts are excellent, but the earlier recording captures the piece in its most uncompromising form. With songs like “Everybody’s Got The Right” and “Another National Anthem,” Assassins remains provocative and incredibly unsettling. It is frighteningly relevant, perhaps more so now than when it first appeared.

1. Sunday in the Park with George (1984)

The top four shows on this list are, in many ways, interchangeable. But Sunday in the Park with George feels like the most ambitious and arguably, the most fully realised. Created with James Lapine, the musical offers a fictionalised account of Georges Seurat painting A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, using the act of creation itself as its central subject. All the while, the show tracks his rocky relationship with Dot, whose image he preserves for all time through his painting. The second act shifts time and perspective, examining those same questions through the artist’s fictional great-grandson as he faces the gruelling task of “Putting It Together.” Few moments in musical theatre move me as profoundly as “Sunday,” the song that closes both Act I and the show itself. Seeing a preparatory study for La Grande Jatte at the Met last year – capturing Seurat in the middle of his process – with Sondheim’s music in my mind was quietly overwhelming. Art in conversation with art. Process illuminating process. It reminded me that Sunday in the Park with George is Sondheim at his most expansive, humane and searching.

Passing Through Our Perfect Park

Even when you seem to have everything, you cannot always find what you want, a truth borne out repeatedly in Here We Are and across Sondheim’s canon. As his final musical suggests, we are often caught between forward motion and reflection, between certainty and doubt. Looking back across his post-Prince works, what emerges is not decline, but refinement, a lifelong pursuit of clarity, detail and truth in storytelling through song. As always, Sondheim leaves us not with the answer to life but with the tools to navigate it: passion, intellect and heart. Through what he has given us, we can find comfort and joy in the fact that everyone needs to face a blank page at some point in their life – and then try to finish a hat.

I don’t know why, and it may of course has nothing to do with the quality of the shows, but I really think Assassins and Passion are Sondheim’s most enjoyable works overall! The only other two shows which I like enough to give them a run for the top spot is Sweeney Todd and A Little Night Music. Having read the script to every Sondheim musical, and seen what I can see, I really don’t understand the fuss over Follies and Into the Woods (even though I thoroughly enjoy both shows!)

But my opinions aside, it was great reading your thoughts again!