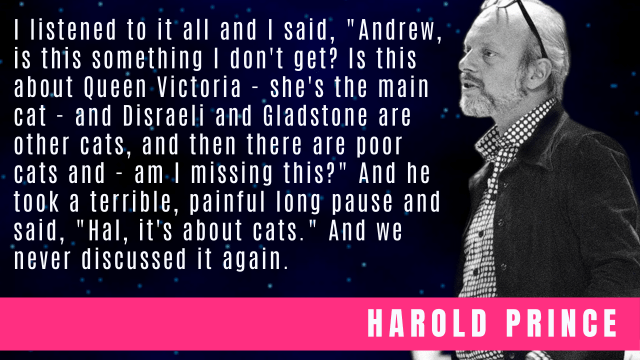

Towards the end of last year, I dipped into What Would Barbra Do? by Emma Brockes, a novelty book that proposes that few situations in life aren’t made better by showtunes. At the end of the introduction, Brockes references a conversation between famed Broadway producer and director Harold Prince and Andrew Lloyd Webber about Cats, which was Lloyd Webber’s next big project. Prince, who had directed Lloyd Webber’s political rock opera Evita, asked the composer whether the show was a metaphor for life in the United Kingdom, with some cats representing figures like Queen Victoria and Benjamin Disraeli and others the general populace. Lloyd Webber replied, “Hal, it’s about cats.” In the end, Prince passed on Cats, and Trevor Nunn would direct what would go on to be one of the longest-running shows both on Broadway and in the West End.

Although Brockes misattributes Lloyd Webber’s words to Cameron Mackintosh, who produced the show, recalling the anecdote reminded me once again of questions we keep on revisiting at a time when revivals of classic shows are more popular than ever – and in fact, when choices made in current productions even end up debated ad nauseam on social media. Who holds the final say when it comes to making meaning in musicals? Do audiences have to believe what the writers say the show is about? Where does the director fit in? What does it actually mean to honour the vision of the creators? And do we actually have to agree about this?

When I – like Princeton from Avenue Q – was studying a BA in English, at one point, I announced to a friend of mine that I thought I was a structuralist. The memory of this somewhat precocious outburst resurfaced as I was considering whether it mattered that Lloyd Webber is on record as saying the show is simply about cats. Such a readerly take on the material seems ironic, given the writerly fandom that has sprung up around Cats, which has layers and layers of sometimes impenetrable interpretation.

That said, if I’m honest, I had to go back and see what structuralism was all about. I unshelved my copy of A Glossary of Literary Terms, the indispensable M. H. Abrams handbook on literary theory, to refresh my memory. Am I, after all these years, a structuralist after all? I’ve certainly dallied with other literary movements over the years. And if I am, how does such an approach help or hinder my reading of musicals? Crisis. Either way, revisiting the theory of structuralist criticism revealed that there are certainly aspects of this movement that resonate with me.

The sense of objectivity it pursues is certainly something that I’ve always espoused. I fully appreciate the idea that, as Stephen Sondheim put it in Into The Woods, ‘nice is different than good.’ I like its focus on semiotics in this pursuit; consequently, I love the idea that for musical theatre lovers, there are underlying signs and symbols that help us make sense of musicals, principles established and refined by all the great musical theatre practitioners from John Gay onwards. I’m excited by the language this gives us to discuss the form, and the power this language affords us to grapple with the idea of why musicals are significant, when so many people write them off as trivial cultural expressions. And I’m excited that there is something relational about all of this, even if it is just to dispel the contemporary misperception that objectivity is purely factual.

If we accept that musicals are an expression of a set of underlying conventions, something that I find very exciting about the performative nature of the genre over time, is how we, as contemporary audiences, sometimes have to negotiate several sets of underlying conventions at once, especially given the rising prominence of revivals over the last half-century. Part and parcel of this is the fact that a musical, like all theatre, is at once multiple things: there is the text itself, and then there are performances of the text. All too often, these are assumed to be the same thing, which is why many “purists” struggle with revivals that treat text like raw material and take things from there, sometimes arriving at a very different expression of the musical’s meaning than what was seen in the original production. This is not to say that every new iteration of a musical is successful in interrogating what it sets out to explore. Consider the 2018-2019 Broadway season as an example: for every Oklahoma!, there’s a Kiss Me, Kate.

Even before I finished typing up that last sentence, I could hear the gasps from people who thought that Daniel Fish’s revival of Oklahoma! was an atrocity or those who prized the noble propositions of that same season’s Kiss Me, Kate over the way were executed. This brings us to one of the clinchers of the deal. You see, dear reader, it’s all right. We don’t have to agree, because we can all thrash out what we think makes these shows and their productions work or not from our positions as interpreters of these texts. We can all consciously and purposefully engage ourselves with scripts, songs, choreography, direction and performance in a way that is at once emotional and impersonal. The designs of the creators don’t need to intrude on those of the theatre-makers, and those of the theatre-makers don’t need to intrude on ours. Maybe Oscar Hammerstein II would have enjoyed debating whether Jud Fry is an incel over chili and cornbread. Maybe he wouldn’t have – but maybe that’s all right. Maybe it doesn’t even matter.

I’m really enthusiastic about the opportunities 2026 will offer to revisit musical theatre classics and experience new shows. I’m also pleased to have clarified some of the things that matter to me when I make meaning out of what I’m consuming in this age of consumable content. In that light, I’d like to think that a production of Cats that finds a way to delve deeply into T.S. Eliot’s yearning for cultural and spiritual renewal has the right to exist in the same world as one that is, as Lloyd Webber proclaims it to be, just about cats.