Today, we celebrate the birthday of musical theatre legend Oscar Hammerstein II. Born into a family who were already notable in theatre history, he would become the most renowned of the Hammerstein clan, not only because of his contributions to musical theatre as a lyricist and librettist but also as a practitioner who pushed the boundaries of what musical theatre could accomplish as an art form. Having collaborated with composers like Rudolf Friml and Sigmund Romberg on operettas like Rose-Marie and The Desert Song, he is perhaps better remembered for his work on Show Boat (which he created with Jerome Kern) and the string of musicals he created with Richard Rodgers, which include Oklahoma!, Carousel, South Pacific, The King and I and The Sound of Music. To mark the 130th anniversary of Hammerstein’s birth on July 12, 1895, let’s revisit ten of his greatest lyrics, each of which gives us insight into the man behind the musicals.

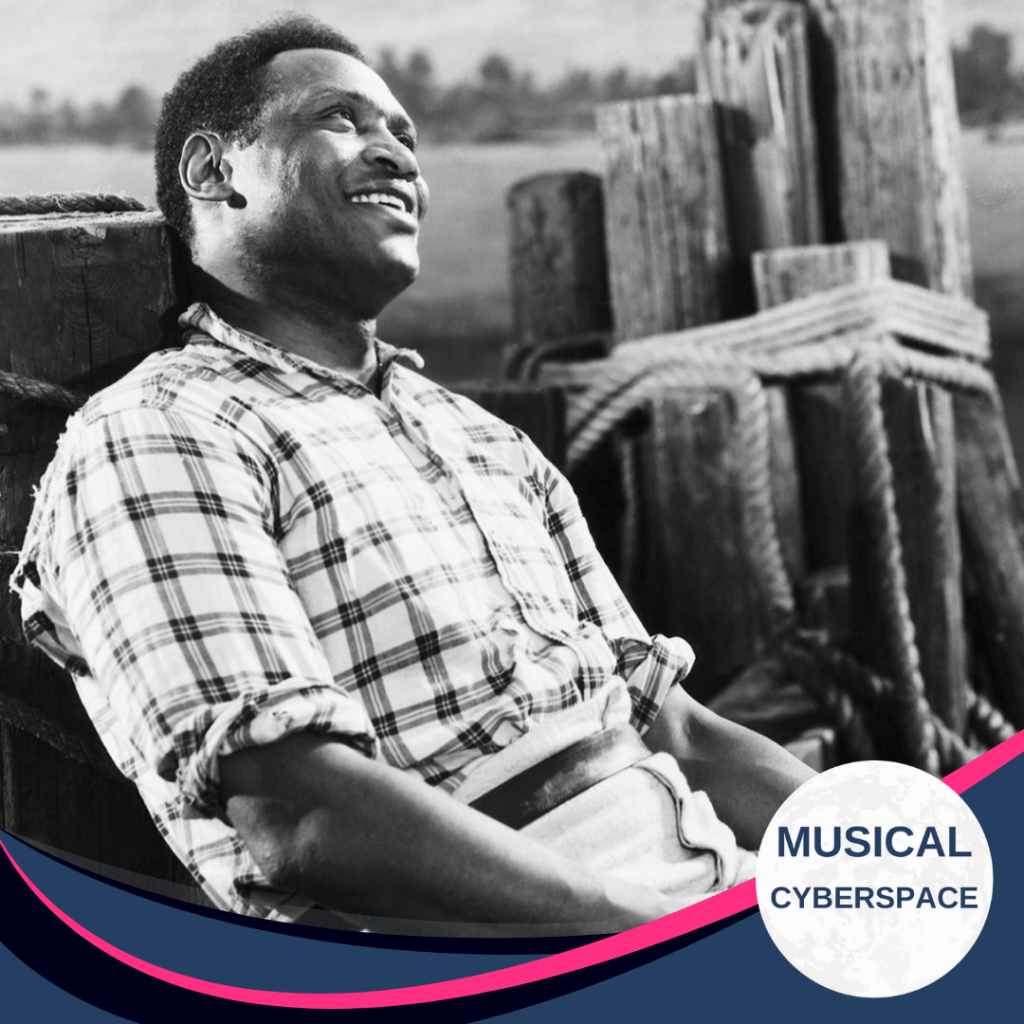

1. “Ol’ Man River” from Show Boat (1927)

Let’s start with one of Hammerstein’s most profound and lyrically rich songs. A landmark in musical theatre history, this lyric gave voice to the struggles of the Black American characters in Show Boat through its poetic central metaphor and its haunting simplicity. The contrast in the lyric between the hardships faced by Joe, a dock worker aboard the Cotton Blossom, the showboat referenced in the musical’s title, and the indifferent continuity of nature is both heartbreaking and timeless. We hear of men who ‘sweat an’ strain, body all achin’ an’ racked with pain,’ while the river, that ‘ol’ man river,’ just ‘keeps on rollin’ along.’ Nature moves forward, indifferent to the injustices endured along its banks. Sadly, almost a century after this song was written, many people remain similarly indifferent to what is happening to those around them.

There’s a great theatre legend about the importance of this lyric, and of musical theatre lyrics in general. At a dinner in the late 1940s, Hammerstein reportedly bristled when Show Boat was referred to as a “Jerome Kern show.” When someone called “Ol’ Man River” a Kern song, Hammerstein replied, “I guess when Jerry Kern wrote the songs, they came out like this” — and then hummed the melody without words. Later versions of the tale attribute the sentiment to Hammerstein’s second wife, Dorothy:

Everyone always talks about Jerome Kern’s “Ol’ Man River.” But Jerry only wrote ‘dum dum dum dum.’ My husband wrote the words that fit those notes – “Ol’ Man River.” Nobody stops to remember that.”

Of course, both stories may be true, but either way, the anecdote is a powerful reminder that in musical theatre, a lyricist plays as great a part in giving a song its soul as its composer does.

2. “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man” from Show Boat (1927)

If “Ol’ Man River” shows Hammerstein’s lyrical poetry at its most profound, “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man” reveals his dramatic precision. On the surface, the song expresses romantic devotion. But when Julie begins singing it to Magnolia, Queenie interrupts, puzzled: she’s never heard a white woman sing this song. Julie dodges the question, and the number quickly builds into a sweeping ensemble, deflecting Magnolia and Queenie’s attention from the matter, just as Julie intends it to do. Even so, the moment plants a seed of suspicion and foreshadows a deeper truth for the audience. A few scenes later, it is revealed that Julie has Black ancestry and is passing as white in a racially segregated society. When the truth emerges, she and her husband, Steve, are accused of miscegenation, and the song’s early appearance becomes more than characterful and entertaining. It marks a turning point in musical theatre, signalling that the genre could engage with complex social issues like race, instead of simply delivering light entertainment.

3. “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin'” from Oklahoma! (1943)

The opening lines of Oklahoma! changed Broadway. Hammerstein, always writing in service of the story he was telling, shared his unexpected inspiration for the lyric of the first Rodgers and Hammerstein song to be heard on stage by theatre audiences: the opening stage directions from Lynn Riggs’s Green Grow the Lilacs, the source material for Oklahoma! “On first reading those words,’ he recalled, “I thought what a pity it was to waste them on stage directions.” His observational and optimistic lyrics ushered in a new era where musicals could begin quietly and build belief in the dramatic world through setting and character rather than spectacle. With its naturalistic imagery and the authentic ebullience of Curly greeting the day, “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin'” delivers a moment of perfect harmony that perfectly sets the drama of Oklahoma! in motion. It remains one of musical theatre’s most quietly radical moments.

4. “If I Loved You” from Carousel (1945)

“If I Loved You” forms part of a wider sequence in Carousel known as the “bench scene,” which set the standard for integration between music and drama in musical theatre for decades to come. Even today, it remains a master class in storytelling. The song itself, inspired by lines of dialogue from Ferenc Molnár’s Liliom, the source material for the show, is a study in emotional repression and yearning, using a conditional “if” to allow Julie and Billy to confess their feelings for one another without admitting their vulnerability. It’s brilliant and heartbreaking, a masterpiece of subtext in dramatic writing. Although the characters sing hypothetically, every line pulses with what they dare not say. It’s the perfect way to set up the dynamic of Julie and Billy’s relationship, and their inability to communicate in this first scene here haunts their relationship as it develops through the course of the show.

5. “Soliloquy” from Carousel (1945)

One of the greatest challenges in creating Carousel was to enable the audience to identify with Billy. His behaviour is alienating, and there didn’t seem to be a way within the standard musical theatre conventions of the time to reveal more of his interior life. Never afraid of innovation, Hammerstein crafted a lyric that revealed Billy’s inner passions and fears upon discovering he would become a father and thereby motivate, if not justify, the choices he goes on to make. When Rodgers set the lyric to music, musical theatre fans were given the gift of a brilliant solo that lasted for almost eight minutes. In the song, Hammerstein charted Billy Bigelow’s emotional arc from excitement through anxiety, fear and finally, conviction with honesty, humour and depth. For an actor able to master the piece, it’s a tour de force.

6. “You’ll Never Walk Alone” from Carousel (1945)

After Billy’s death in Carousel, Nettie comforts the grieving Julie with a simple message of endurance: “You’ll Never Walk Alone.” What began as a moment of intimate reassurance within the plot of a 1940s musical became one of the most beloved anthems ever written for the stage. Hammerstein’s lyric is spiritually resonant, morally grounded and emotionally direct, qualities that allowed it to transcend its theatrical roots and become a cultural touchstone. It has been recorded by artists from Patti LaBelle and Elvis Presley to Aretha Franklin and Marcus Mumford, and has charted multiple times on the Billboard 100. Adopted as the official anthem of Liverpool Football Club, it has echoed through stadiums and rallies, as well as at vigils and funerals. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it resurfaced as a song of solidarity for frontline workers across Europe. Few lyrics have travelled so far or meant so much to so many people, a testament to Hammerstein’s extraordinary ability to speak directly to people’s souls.

7. “You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught” from South Pacific (1949)

Few lyrics in musical theatre history are as brave or as succinct as “You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught.” Sung by Lieutenant Cable in South Pacific, the song exposes the fact that racism is not innate, but passed down to children by parents and society, a startling idea for a Broadway audience in 1949. Rodgers and Hammerstein insisted on keeping “You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught” in the show, despite fierce backlash. When South Pacific toured the American South, some lawmakers tried to ban the musical altogether, accusing the show’s creators of promoting a Communist agenda. But for Hammerstein, the lyric was the entire point of the show, an indictment of learned hatred that one generation insidiously teaches to the next. His courage paid off. The song remains one of the most socially charged in the musical theatre canon, its message as urgent now as ever: racism must be actively unlearned if any social justice is to be achieved in our time.

8. “This Nearly Was Mine” from South Pacific (1949)

Many people would expect “Some Enchanted Evening” to represent South Pacific on a list of Hammerstein’s greatest lyrics. While its sweeping romanticism has earned the song its iconic status, “This Nearly Was Mine” offers something rarer: a mature and restrained expression of heartbreak. Whereas “Some Enchanted Evening” idealises love at first sight, “This Nearly Was Mine” mourns a love that almost was, with emotional sophistication not always evident in Golden Age Broadway ballads. The lyric is lean, avoiding cliché while evoking longing, loss, dignity and regret. It builds incrementally in its imagery until the emotion peaks, sitting perfectly on a melody that deepens what the words have said. Stephen Sondheim, who criticised the lyrics for “Some Enchanted Evening” for their generalities, often praised Hammerstein’s ability to communicate a sentiment without being sentimental. That quality is on full display here, shifting Emile from being an archetypal romantic hero to a vulnerable man facing irrevocable loss.

9. “Climb Ev’ry Mountain” from The Sound of Music (1949)

“Climb Ev’ry Mountain” may seem an unexpected inclusion on a list of Hammerstein’s greatest lyrics. Some might dismiss it as generic, but its impact, both within The Sound of Music and far beyond it, is undeniable. As the show’s moral and emotional spine, the lyric urges Maria, as well as audiences of the show, to pursue their purpose with clarity and courage. Stirring and sincere, the song embodies Hammerstein’s gift for spiritual upliftment without religious dogma, offering a universal message of resilience, aspiration and faith. Over time, it has transcended the musical, becoming a staple at graduations, memorials and moments of personal reckoning. I’m sure that many of us have played it in our cars or on our devices at key moments of our lives. It’s pure Hammerstein optimism, distilling the idealism that runs through all his work into a single call to action: keep going, no matter how hard the climb might be.

10. Edelweiss from The Sound of Music (1959)

“Edelweiss” was the final song written by Rodgers and Hammerstein, and the last complete lyric Hammerstein completed before he passed away in 1960. Written during the Boston tryouts for the show, “Edelweiss” was conceived as a song that captured Captain von Trapp’s sense of loss as the Austria he knew and loved in the wake of the German annexation of Austria. Much to the frustration of many Austrians, some of whom view the song as kitsch or clichéd, the song has often been mistaken for an Austrian folk song. That said, “Edelweiss” is so effective and all the more profoundly moving because it is so delicate and deceptively simple. A quiet affirmation of homeland and heritage, “Edelweiss” becomes, in context, a protest song disguised as a lullaby. Rodgers was, in fact, so clear in his convictions about the song’s intent that he never granted permission for the use of the “Edelweiss” melody with adjusted lyrics for commercial purposes. The Rodgers and Hammerstein estate remains compliant with these wishes even today, maintaining the integrity of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s intentions in writing the song.

Honourable Mentions…

There are so many great Hammerstein lyrics, that it’s hard to curate a list of only ten. In addition to those discussed above, there is, for example, “All The Things You Are,” from Very Warm for May. Though the melody by Jerome Kern is iconic, Hammerstein’s introspective lyrics are just as exquisite, an ode to idealised love, written with poetic phrasing that has made the song popular as a jazz standard.

A lyric like “I Can’t Say No” from Oklahoma!, in which Hammerstein’s ear for character is evident, also warrants mention. The song characterises Ado Annie in a comic and charming way, while hinting at deeper themes like sexual agency and social expectations.

A further offering from Carousel is the brilliant “What’s the Use of Wond’rin’?” This lyric is quietly provocative, wrestling with what it means to love someone flawed. Its resigned, almost fatalistic tone makes it as troubling as it is tender, perhaps more honest than many a Broadway love song.

In The King and I, “I Have Dreamed” is a dreamy and sensual song that conveys intimacy through imagination, which makes it even more romantic and prepares the audience for the tragedy that awaits Lun Tha and Tuptim. It’s an excellent example of how to set things up for a moving reversal of fortune.

In the same show, “Getting to Know You” offers a psychologically astute observation with childlike simplicity, helping to chart the growing trust between Anna and the King’s wives and children with the kind of grace Hammerstein exemplified in his everyday life.

The list goes on… “So Far” from Allegro, “All at Once You Love Her” from Pipe Dream, “Ten Minutes Ago” from Cinderella, “Love Look Away” from Flower Drum Song – it’s hard to stop listing the lyrical joys of Hammerstein’s body of work.

Final thoughts…

While known for crafting some of the greatest stories and lyrics in musical theatre history, it is not only his own words that speak to Hammerstein’s legacy. He famously mentored another top-tier musical theatre practitioner, Stephen Sondheim, who would go on to be another mover and shaker in the musical theatre genre. That said, perhaps the anecdote that gives us the most insight into who Hammerstein was, is the story Mary Martin told about a lyric he passed to her after it was known he was fatally ill with stomach cancer.

One day I was getting out of the car and going into the theatre when I saw Oscar coming out of the stage door. He didn’t see me. He was walking sort of bent over for him – and he didn’t look at all well. Then he saw me and he straightened up. He had a little piece of paper in his hand, and he said, “Here are the words for the scene between you and Lauri. Dick already has the music. We’re adding a verse to “Sixteen Going on Seventeen”. I would have loved to enlarge it and make it a complete song, but we’ll have to use it this way

now. Don’t open it yet. Just look at it when you have time.”Then later on Dick Rodgers came to my dressing room and he said, “Did you see Oscar?” I said yes, and he said, “Well, Mary, you’re a big girl now, and you’re old enough to take things. I have to tell you that Oscar has cancer and it’s really bad. He didn’t want to tell you himself, so he asked me to tell you. But he’s given you the lyrics?”

I said he had, and Dick said, “Now, we’re not going to be sad about this, Mary. We don’t know how long he will be with us, but he will work to the very end. If you feel badly, stay in here for a while, and then come out and rehearse and forget it. We’re all going to forget it and that’s it.”

I opened the piece of paper Oscar had given me. This is what it said: ‘A bell is no bell till you ring it. A song is no song till you sing it. And love in your heart wasn’t put there to stay. Love isn’t love till you give it away.’

Happy birthday, Mr Hammerstein! Thank you for everything you’ve given us.