Although the Tony Awards represent the pinnacle of each Broadway season’s theatrical presentations, some recipients of the award for Best Musical haven’t stood the test of time. Sometimes, an undeserving musical edges out a show that is otherwise recognised as being absolutely brilliant; at other times, an older show is out of step with the way we see the world today. There are even cases where the craft of creating musical theatre has just developed so much that a past winner seems to lack the nuance of one of its contemporaries. In today’s Saturday List, we’re taking a look at a selection of musicals that may have been representative of their time, but which perhaps aren’t classics for all time.

5. Kismet (1953)

There was an audience for Kismet in the 1950s, but it is virtually unrevivable now. A Middle Eastern fantasy set in the time of The Arabian Nights, the show tells a tale of stereotypical characters in caricatured settings, an approach that clashes sharply with our modern sensibilities about representation. Kismet follows the exploits of a clever poet, Hajj, and his beautiful daughter, Marsinah, who become caught up in a series of palace intrigues involving mistaken identities and arranged marriages, all under the guiding hand of fate. The show opened to no reviews due to a newspaper strike and received mixed reviews a week into its run once the strike ended. Still, its pseudo-classical score adapted from the works of Alexander Borodin by Robert Wright and George Forrest, the glorious pageantry of Lemuel Ayers’s designs and a distinguished central performance by Alfred Drake as Hajj won over both audiences and members of The American Theatre Wing. The only other show that might have given Kismet a run for its money was the second biggest winner of that season, Can-Can, which also drew lukewarm reviews from critics, although it was popular enough with audiences to sustain a run of 892 performances.

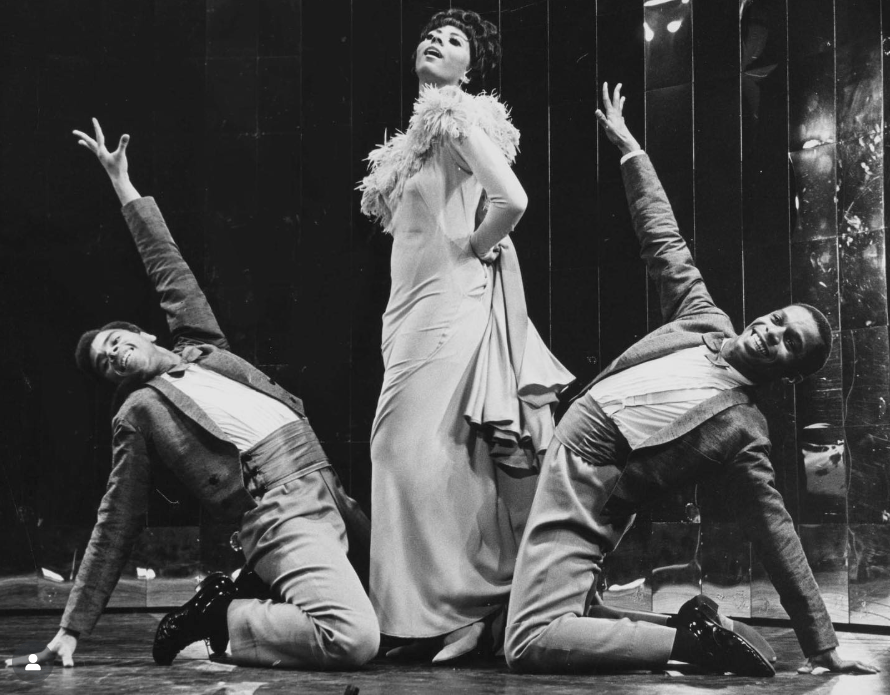

4. Hallelujah, Baby! (1967)

“The show was a turkey,” Arthur Laurents said about Hallelujah, Baby! “I don’t think it had much to say.” Following the life of Georgina, an African American woman, across several decades, in an attempt to explore the dynamics of race and racism in the twentieth century, some might argue that this kind of show actually has a lot to say. Despite its admirable intent, the more likely problem faced by Hallelujah, Baby! was the white lens through which the show’s narrative was filtered. All of its creators, including Laurents himself as well as Jule Styne, Betty Comden and Adolph Green, have several undisputed hits on their respective résumés, but what is conspicuously absent from this creative team is an authentic Black voice. Through its simplification of structural oppression into a sequence of personal triumphs for Georgina, Hallelujah, Baby! ends up embodying a worldview that reads as naïve at best and patronising at worst. Hallelujah, Baby! is rarely revived, and its obscurity limits its impact today. Laurents revised the show in 2004, helming a production that had its eye on Broadway. The show still lacked the bite it needed, confirming that what held it back all along was ideological, not just aesthetic. As such, it remains a fascinating failure rather than a timeless triumph.

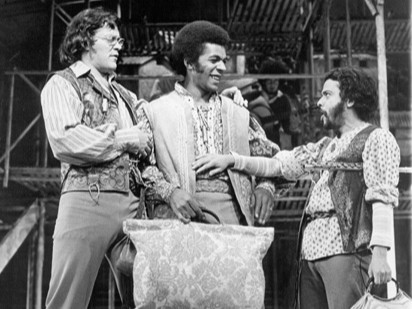

3. Two Gentlemen of Verona (1971)

Is Two Gentlemen of Verona the Tony Awards’ most infamous misjudgement? This rock adaptation of Shakespeare’s early comedy somehow beat Follies and Grease to the Best Musical prize. Did its chaotic, countercultural energy simply overwhelm all of the voters? There’s very little in John Guare and Mel Shapiro’s book, in which young Proteus and Valentine put their friendship to the test as they journey through romance, betrayal and reconciliation, that can be played today without any sense of irony. And while I’m sure that the audiences of 1971 thought that numbers like “Thurio’s Samba,” “What Does a Lover Pack?” and “Don’t Have the Baby” were a bop, nothing from the score (with Guare’s lyrics set to music by Galt MacDermot) had a significant impact on the canon. With no traction for modern productions – The New York Times critic Ben Brantley called a 2005 revival ‘festive,’ while noting that it opted for ‘nonsense over sensibility’ and that the songs were ‘clunky’ – it’s little more than a relic of its time. With its amateurish exuberance laid bare, it’s little wonder that Two Gentlemen of Verona is often cited as one of the baffling Best Musical wins.

2. Contact (2000)

There was one big problem with Contact being named the first “Best Musical” of the twenty-first century – it’s not a musical. With no live singing, this was a modern ballet, and it had no business being nominated in the category, let alone winning it. Is there anything wrong with the show itself? Not at all. In fact, it’s quite a good dance production, and it was certainly worthy of all the praise it received and its triumphant 1 010-performance run. So why complain? For one thing, it stripped the true best musical of the season – The Wild Party – of a title it deserved and a legacy to which it was entitled. Written by George C. Wolfe and Michael John LaChiusa, The Wild Party was a dark and complex musical that managed to simultaneously capture the neurosis of the world’s Y2K shift as well as the spirit of its 1920s setting and its source material, Joseph Moncure March’s eponymous poem. Contact’s win signalled something troubling, albeit not something we haven’t seen before or since: a moment when Tony voters appeared uncertain about what, exactly, the awards were recognising. In that sense, Contact stands less as a triumph of innovation than as an early warning sign of an awards culture increasingly willing to blur its own definitions in pursuit of marketing potential.

1. Memphis (2009)

Despite two undeniably committed central performances from Chad Kimball and Montego Glover, Memphis is a curiously dull show. David Bryan and Joe DiPietro crafted an oversimplified take on race, music and rebellion that already feels dated less than two decades after its Tony win. Framing the birth of rock ’n’ roll through the familiar lens of a white male liberator makes it feel like the show exists in a world where Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton was never overshadowed by Elvis Presley in the 1950s. The racial politics of Memphis are blunt rather than interrogative, offering reassurance instead of challenge, while its derivative score and glossy staging prioritise momentum over depth. What stings more is the context of its victory: the following season saw the arrival of The Scottsboro Boys, a daring and politically urgent work that grappled directly with American racial injustice, only for it to be largely sidelined while Broadway’s attention shifted to the juggernaut that was The Book of Mormon. In retrospect, Memphis is less a bold statement about cultural change than an emblem of 2010s Broadway populism, a reductive tale of racism in the music industry that is as tone-deaf as it is inert.

Looking Back to Find the Way Forward

Reflections about which musicals have aged well or not always involve a degree of subjectivity, but it’s not merely a matter of personal taste. Awards like the Tonys are institutional endorsements, reflecting what Broadway chooses to celebrate, legitimise and canonise at a given moment in time. Revisiting these decisions allows us to see how theatrical styles change as well as the way attitudes toward representation, authorship, form and power either evolve or fail to keep pace. To interrogate these winners is not to diminish the artists involved, but to better understand the blind spots of the industry that rewarded them, especially when we view them in the light of our contemporary values and developing theatrical practices. Which Best Musical winners do you feel haven’t aged as well as we’d like to think? Head to the comments section below and let us know!